The Case of the Multimeter Meltdown

The scene

In the 1990s, the facility underwent an electrical retrofit (performed by outside contractors) to get rid of some of the most outdated electrical switchgear and clean up the remainder of the electrical infrastructure. Another outside contractor maintained services for high-voltage electrical equipment required to power a freezer.

The master electrician had previously served as an outside contractor and performed electrical inspection work at the site prior to being hired as a full-time employee at the warehouse. Although his staff of two assistants had some electrical training, they were not licensed electricians.

The accident

On the day of the accident, the warehouse manager, who was the electrician’s direct supervisor, was involved with welding work on the roof of the facility. After being notified there was an issue with the UPS, he asked the electrician to investigate the situation, advising him to trace the problems through the on-site electrical system and report back.

Upon his initial investigation, the electrician found some minor problems, such as dirty contacts on high power switchgear and capacitors (which he cleaned), and voltages sagging below their nominal value (but nothing significant enough to merit fixing). He worked fast because he wanted to get back and check on his staff, who were in another part of the plant performing routine maintenance. For safety reasons, he judged all voltages to be below 600V (nominal AC RMS); therefore, he wore gloves rated at a nominal value of 600V.

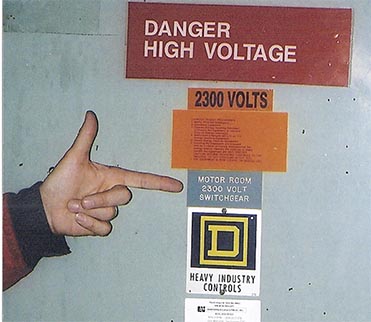

He went to a lower level floor of the facility, which was the size of a football field and housed dozens of electrical closets. While he was there, he opened one cabinet that contained live circuits at 2,300V, RMS AC 3-phase. On this door — and an adjacent door to the same closet — there were a few small signs indicating the high voltage level, but the electrician unfortunately overlooked them as he went from one electric closet to the next checking voltages. At one point in time, there had been many large signs (affixed by adhesive) on the doors indicating the 2,300V rating of the circuits contained within. However, these were all missing on the day of the accident. (At the time of the incident, there was a gummy residue on the doors where the large signs had been, but the original large signs themselves were never found.)

The lawsuit

After the accident, the victim initially collected workman’s compensation and then began the difficult task of healing. Approximately five or six months later, the plaintiff and his wife sued the owners of the warehouse, which proved to be six different parties, including the building owner, parties renting the building for use as a food warehouse, and the electrical contractor who had done the retrofit. The owner wanted to sell the building; however, he could not do so until he was removed from the pending lawsuit. Therefore, he hired a law firm that, in turn, brought us in as forensic engineering experts to investigate the case.

Investigation and analysis

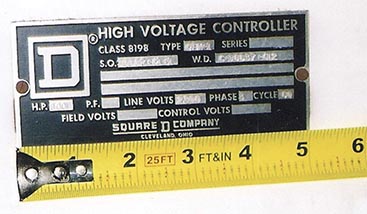

When we visited the site, it was almost a year after the accident had occurred. By then, new signage had been put up on the high-voltage cabinets in question. Hence, the photos in this article show the new signage, which was probably very similar to what was actually missing on the day of the accident. In Photo 2, there is a small aluminum sign with a black background, which was present on the day of the accident. This sign, which is blown up in Photo 3, does clearly indicate the 2,300V designation, but it is still difficult to read quickly. Also small, the grey-white sign in Photo 4 was in place on the day of the accident.

The plaintiff testified that he had assumed the voltage was nominal 480V or less and had no idea there was even a 2,300V source in that part of the building. He knew that the 2,300V source existed in a small building apart from the main warehouse that served the massive refrigeration units. However, because a private contractor was responsible for monitoring and maintaining this isolated building, he assumed any direct electrical hookups and monitors were all in the small building — not in the main warehouse.

The bottom line was that the job he was tasked with did not require him to be in this area of the warehouse in the first place. He would have known this if he had looked at the existing wiring diagrams. In addition, the plaintiff failed to inform his supervisor of the areas he planned to troubleshoot beyond those originally assigned. The warehouse supervisor, who depended on an outside contractor for maintenance of the 2,300V electric source and the electric closet located within the warehouse (aka, the closet where the accident occurred), would have informed the electrician that it was this contractor, not the victim, who was responsible for the control of the accident cabinet. If this wasn’t enough, there were two more factors the plaintiff failed to take into account.

He testified he was measuring the phase-to-phase voltage. This is the wrong protocol for troubleshooting a 3-phase circuit. The phase-to-phase voltage is generally not significant in the original trace of a troubled 3-phase circuit. The proper protocol when measuring an unknown phase voltage in a 3-phase system is to place the ground or common lead of the multimeter on the nearest ground point and then clip the hot lead of the meter to one of the bus bars. Had the plaintiff done this, there would most likely have been no accident, or there would have only been damage to the multimeter. In this case, the phase-to-ground voltage was 2,300V, while the phase-to-phase voltage was almost 4,000V.

The conductors and couplings of the 2,300V service were of a very large size — significantly larger than the ones that the electrician saw in the other electrical closets for voltages of 600V or less. This should have been an additional red flag for the plaintiff to rethink his next move. When asked about this, the plaintiff said he thought the wires and couplings for the 2,300V source were greater than normal size only because they were low voltage and high current, not the high voltage 2,300V.

The victim’s work boots and gloves were sufficient for voltages that he was authorized to work on (i.e., 440V to 480V). These two PPE items most likely saved him from electrocution and possibly death. He did, however, sustain very bad burns. And although he recovered, he died one year later from complications of his injuries.

The findings

Based on our investigation, we determined with a reasonable degree of engineering certainty that this accident involved gross negligence on the part of the plaintiff. We maintained that he was ultimately responsible for the accident because he did not behave in a professional manner or follow the proper protocols, including:

- He did not obtain the available wiring information.

- He did not have approval to work in that part of the facility.

- He did not read the signs that were on the subject cabinet.

- He did not de-energize the circuit he was investigating.

- He did not follow proper troubleshooting protocol of measuring the phase-to-ground voltage rather than the phase-to-phase voltage.

We also found gross negligence on the part of the outside contractor, who completed the retrofit at the warehouse, for not providing proper signage for the subject cabinet. Furthermore, this contractor failed to ensure that the electrical interlock of the incident cabinet was in place and functioning properly.

The outcome

The plaintiff did receive accident benefits and workman’s compensation, but his lawsuit against the warehouse owner took two years to resolve. Because he died within the first year after the accident, his widow continued the suit. According to the laws of the state in which this accident occurred, legal suits of this type went to a governmental review board to deem them worthy or not worthy to go to court. The review board dismissed the case without prejudice. The widow collected nothing from the owner; however, we were told she was bringing another suit against the contractor who serviced the electric closet and the 2,300V supply. Because we were retained by the owner, our interest in the case ended with this judgment.

Hmurcik is a consultant at Lawrence V. Hmurcik, LLC. He can be reached at hmurcik@bridgeport.edu Patel is presently a freelance consultant and instructor at the University of Bridgeport. He can be reached at saroshp@bridgeport.edu.